Breakfast at Tiffany’s —

When 20-year-old Hannah Westworth went from 196 pounds to 105 pounds within two years, friends and family commented on how good she looked. Born without a pituitary gland, which regulates growth and thyroid function, Hannah struggled against a lifetime of medical issues, including digestive issues.

The condition, known as hypopituitarism, can cause weight gain, and at 17 years old, Hannah had already dealt with the cruelty that all fat kids are subjected to: “I have had to deal with a lot of comments and teasing over my weight and size.”

In March 2009, Hannah was rushed to the hospital with asymptomatic abdominal pains and was released two weeks later with strong painkillers and no diagnosis, although some doctors suspected a psychological or eating disorder. A month later she returned with sever pains and vomiting, and over the course of weeks became severely dehydrated and malnourished, losing over one pound per day.

Finally, doctors settled on a diagnosis: gastroparesis, or stomach paralysis.

Nothing Hannah ate was being pushed through her intestines, so she began to starve. Hannah says, “For more than two years I’ve been dying slowly.”

At 5’6″, Hannah had a BMI of 31.6, making her obese prior to the gastroparesis, and she currently has a BMI of 16.9, making her underweight.

Based solely on BMI, complete strangers would judge her as healthy, particularly when compared to her heavier weight. But despite the medical emphasis on the current trend of higher BMIs, Body Mass Index is not an indicator of health.

Yet, BMI is the primary metric by which our health and value is judged. As I wrote last week, in many cases when studies look at the cost of treating obese people, the only indicator that weight played a role in the illness being treated is whether the patient received a secondary diagnosis of obesity. One of our readers, Fab@54, shared her own experience of being diagnosed obese while on a routine checkup.

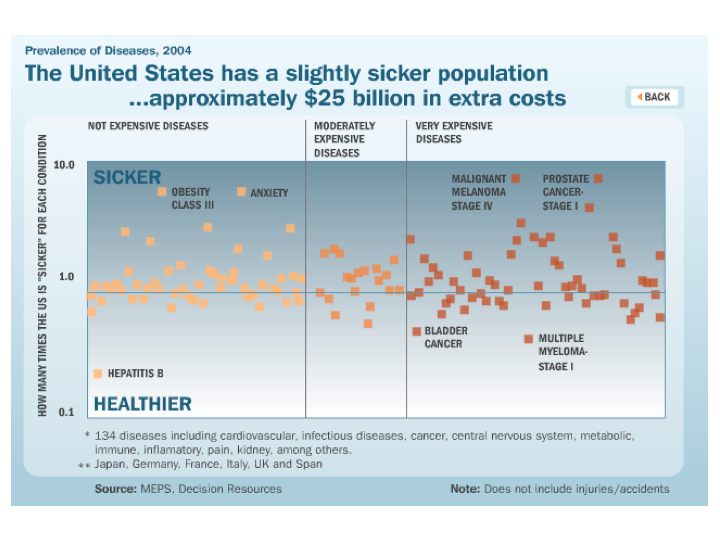

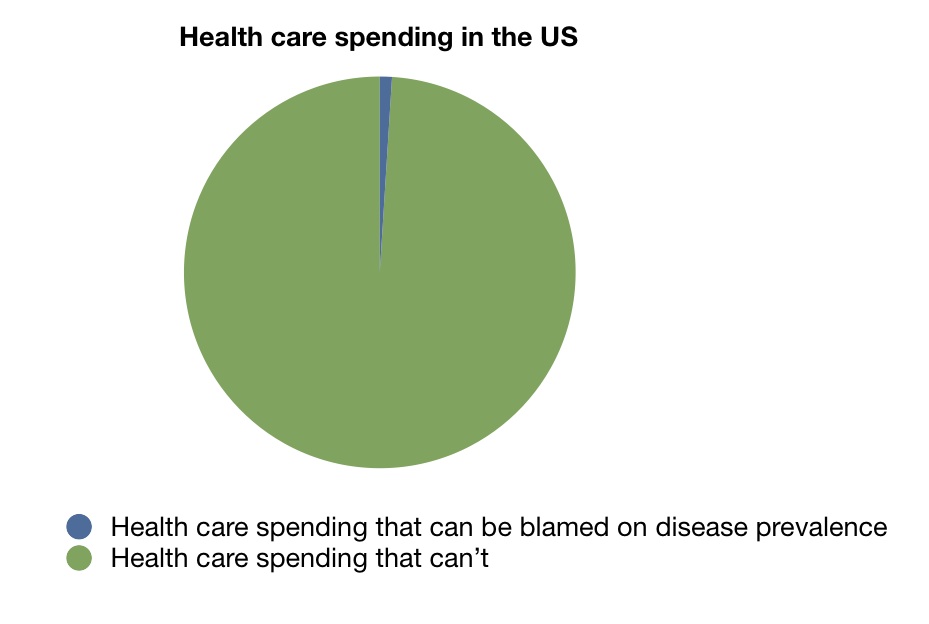

Yet the costs of obesity are relatively small compared to most diseases:

While the actual amount we spend on treating diseases, $25 billion, is just a sliver of where our healthcare costs are coming from.

Yet BMI and weight are emphasized as the most important measure of health that we can use. Yet while Hannah’s body induced the kind of weight loss that millions can only dream of, her health suffered immensely and she endured horrific physical pain.

“I’ve really been to hell and back,” says Hannah. “Since 2009 I’ve been given many different anti-sickness medications, and also had countless endoscopies and ultrasound scans. I’ve been fed via feeding tubes into my lower bowel.

“I’ve lost my independence, have struggled with my job and have become almost housebound.”

Hannah is now raising £20,000 to pay for a digestive pacemaker that will help get her stomach moving again. If you can donate to help her, please do.

The same day I read Hannah’s story in the Daily Mail, I noticed another, seemingly unrelated, headline: “Is Audrey Hepburn the key to stopping the obesity epidemic?“

Intrigued, I read further.

Audrey Hepburn, iconic star of Breakfast At Tiffany’s, was renowned for her waif-like figure. But her sylph-like beauty masked a lifetime of poor health which culminated in her death at only 63… Hepburn, 16, was reduced to eating tulip bulbs and trying to make bread from grass. She spent the war’s closing days hiding from the Nazis in a cellar.

Wait a minute… the cure for obesity lies in Nazi occupation? Say what?

During the Dutch hunger winter of 1944-1945, produced a natural laboratory to study severe caloric restriction, as rationing limited their daily caloric intake to less than 1,000 calories. Of particular interest, the study of epigenetics, or the way genetic inheritance can be altered by the environment, benefited greatly from the famine.

While the hunger winter survivors’ babies tended to be born at a normal size, they often inherited a lifetime problem: their obesity rates are much higher than normal.

Some theories suggest that when a baby suffers malnutrition in the womb, a survival mechanism kicks in that pre-sets its metabolism in preparation for being born into a world of famine and starvation. This epigenetic alteration causes the body to give priority to fat storage over a developing robust liver, heart and brain.

Of course, now that the medical community is emphasizing that obese women who are pregnant should gain zero pounds while pregnant, it is completely baffling that researchers have absolutely no reservations about experimenting on fetuses with Metformin.

Once again, it is weight that is the metric of health, rather than the effect that these kind of in utero nutritional interventions may have that are of the utmost importance.

And while the gestational impact of the Dutch hunger winter have taught us nothing, the story of Hepburn’s health reflects society’s bizarre disconnect between weight, beauty and health.

As with Hannah, our society chooses to look at Hepburn’s waistline, rather than her lifeline:

Hepburn’s slight figure — her waist was only 20in — came not from any celeb-style fad diet. It was a legacy of the jaundice, anaemia, respiratory problems and chronic blood disorders she contracted in those desperate days.

And yet, two years prior, the Daily Mail was boasting of the Audrey Hepburn Diet, and a search for “The Audrey Hepburn Diet” yields promises of pasta and chocolate every day!

Such is the danger of focusing so intently on weight over health: nobody wants to peek under the surface of our thin-centric culture. Modern rail-thin celebrities are epitomized as the American health ideal, despite their likely correlation with eating and exercising disorders, drug addiction, and a whole host of unhealthy behaviors meant to keep them slim for as long as possible.

Rather than focusing narrowly on body size or shape, let alone BMI, society would benefit greatly from a culture that emphasized healthy behaviors and a balanced approach to healthcare.

But if we continue down this path of emphasizing weight in place of overall health, we may someday see promises to cut our weight in half using the highly effective treatment of medically-induced gastroparesis.

This is such a great and tragic example of one of my pet peeves about the hysteria over childhood obesity and the obesity epidemic in general. When a campaign targets the health of only one segment of the population and the primary criteria is their weight, thin people are automatically assumed to be healthier than fat people. The result is stigmatization of fat people and lack of awareness of healthy lifestyle choices for thin people.

Exactly… so much focus and energy has been poured into preventing obesity, that we may be missing out on the opportunity to encourage real preventative health care programs for all Americans. When weight is our metric of health, then we all lose.

Peace,

Shannon

And when a fat person loses a large amount of weight, most people see that as good, even if the person isn’t dieting and/or trying to lose weight. Even some doctors don’t see that as problematic and think it’s good, therefore they don’t look to see if there’s a reason for unexplained weight loss until one has lost so much weight that one is in danger of starving to death - then it’s a problem, but not until one is nearly dead.

This obsession with being thin at any cost has got to stop, it’s costing too many lives, and every one of those lives is irreplaceable.

vesta,

Most studies on weight cycling go out of their way to distinguish between intentional and unintentional weight loss. Same with studies of health and weight, particularly when it comes to the underweight category, where they put huge caveats to remind people that their weight may be a result of some underlying disease. So, researchers understand the difference, but society as a whole completely ignores it. Weight loss always equals good in our culture, until a problem is diagnosed. Then we might step back and say, “Oh, nevermind.”

But even intentional weight loss is fraught with risks. The biggest risk factor for weight gain (over 4 pounds in a year) in middle-aged women according to this two-year study is recent weight loss. Women who have recently lost weight are five times more likely to gain over 4 pounds a year than women with a stable weight. And other studies suggest that weight cycling changes body composition away from visceral (“good”) fat and toward subcutaneous (“bad”) fat.

But ignore the data and focus on one thing (thinness) and you’ve got a false sense of hope for skinnies and fatties alike.

Peace,

Shannon

What counts as health care spending based on disease prevalence?

Curing diseases?

Managing diseases?

Actions to prevent diseases?

Disease research?

And as health care spending not based on disease prevalence?

Bureaucracy?

Treating/preventing/managing accidents?

As far as spending more than other countries is concerned, how do our survival rates for particular diseases compare to theirs? How about the improvement of the quality of life if the disease is incurable?

How would you even measure the cost of these? For example, is public sanitation included in health costs? It certainly prevents or drastically lowers the incidence of certain diseases.

——————————————————————-

Hannah’s predicament is sad and the way she’s been treated (regarding weight) is quite frustrating, What I am finding most poignant about the photos is her necklace, which is choker-size in the first picture and hangs down several inches in the second one.

Mulberry,

Each study sets up their own parameters, but most of them are simply counting obesity as a secondary diagnosis (which is the simplest method from a researcher’s standpoint). Others count all metabolic disorders as a consequence of obesity. As far as I know, there aren’t any studies that dig as deep as your (likely rhetorical) questions. And, hell, what about the cost-benefit of improving food security, which also leads to obesity.

Hell, take obesity out of the equation and replace it with sedentary lifestyle and I bet you’ll find even more staggering costs shared by all Americans who are by and large a sedentary people, regardless of size. It’s just that some have the genes to be sedentary and thin, while others are sedentary and fat. But the underlying health issue is not how you look, but what you do, and that goes completely ignored, or else scapegoated onto fatties.

I hadn’t noticed the choker… amazing.

Peace,

Shannon