Unashamed Glutton —

Trigger Warning: Discussion of ridiculous historical diets.

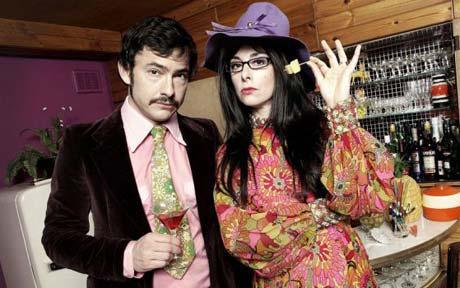

This is Gile Coren: writer, food critic, and “unashamed glutton.”

At least that’s how he describes himself.

Giles is joined by performer, broadcaster and part-time vegetarian, Sue Perkins.

Together, Giles and Sue host one of the most unique, entertaining and fascinating shows on British television today, “Supersizers Go…”

The premise is simple, though the execution elaborate and fanciful: in the first season, Giles and Sue take us on “an extraordinary journey exploring the dining habits of the last 500 years.”

Each week, the pair immerse themselves in the clothing, culture and, most importantly, cuisine of a particular period, from the 17th Century Restoration…

… to the relatively modern 1970s.

I cannot recommend this show enough. Giles and Sue have an amazing rapport, despite having never worked with each other prior to this project. At first, I found them both a bit grating, but like the rich, over-the-top dishes they’re served, I began to not just tolerate them, but to thoroughly enjoy their unique perspectives and caustic senses of humor.

After several episodes, they begin to feel like friends you’d want to invite to your dinner party, but instead they’re inviting us to join them on a historical/hysterical quest to breathe life into the dusty pages of time. I cannot recommend this show enough.

Supersizers began as part of a BBC series called, “The Edwardians — the Birth of Now,” which explored the Edwardian period when King Edward ruled between 1901 and 1910. When Queen Victoria died in 1901, so did the prudish, teetotalling Victorian era.

In her place, King Edward stepped in and inspired our modern culture of extravagance, elegance and sensual pleasures, particularly in terms of diet. The Edwardian era saw the rise of 12 course meals and restaurants, and the return of drunkenness and debauchery.

In 2007, Giles and Sue hosted a segment called “Edwardian Supersize Me,” which, like the Morgan Spurlock pseudo-documentary “Supersize Me,” would throw the pair into this culture of excess and see what effect it would have on their physical, psychological and emotional health.

The episode begins with a visit to a physician, who gives them a check up and explains what to expect from their Edwardian diet. Then for seven days, the pair dress the part of an upper class Edwardian couple, dining on some of the most popular dishes of the day.

For example, the first day’s menu, which is rather modest compared to the rest of the week, looks like this:

Breakfast

Porridge

Sardines on toast

Curried eggs

Grilled cutlets

Coffee

Hot chocolate

Bread, butter and honey

Lunch

Kidneys

Mashed potatoes

Macaroni au gratin

Boiled ox tongue

Afternoon tea

Coconut rocks

Fruit cake

Madeira cake

Bread, butter and toast

Hot potato scones

Dinner

Oyster patties

Sirloin steak

Braised celery

Roast goose

Potato scallops

Vanilla soufflé

You may notice that the only vegetable on the menu the entire day is celery, which becomes a familiar theme throughout the series. It seems that throughout much of history, refined cultures viewed vegetables with suspicion and derision.

Chef Sophie Grigson describes this first day’s menu as “a not-very-grand day’s supper.” She also explains that much of this food is meant to go to waste as a demonstration of the household’s wealth, but even so Giles manages to consume over 5,000 calories on his first day. It’s no wonder that he feels terrible that night and seeks out an Edwardian cure for invalids and convalescents.

The cure? Raw beef tea, which is just as horrible as it sounds.

The Edwardian era saw the first real rise in obesity rates, followed by the first real public health campaigns to combat it. And then, just as today, those got fat on the Edwardian diet were encouraged to follow “crazy diets.”

So on their second day, Giles and Sue partake in the latest dieting fad, Fletcherism.

American Horace Fletcher introduced Fletcherism, which taught that ”mastication is the key to proper digestion.” Fletcherizers would chew each bit of food 32 times, theoretically allowing one’s saliva to breakdown the food before swallowing, which had the added benefit of reducing caloric consumption. Fletcher’s books on the Chew Chew Diet made him millionaire during its brief, but brilliant popularity.

Giles even says that the King took to the diet. “Even Edward the seventh was said to be a fan,” Coren says, before the camera cuts to this painting and zooms in on his belly.

“… but appearances would suggest otherwise.”

Giles and Sue followed the prescription for one meal, lowering their heads in the manner of a Fletcherizer and chewing each bite thoroughly. By the end of the meal, both hosts were done with the short-lived weight loss plan and, as Giles says, “The fad was over by 1910, and I’m not surprised.”

“Edwardian Supersize Me” was so popular that the BBC commissioned a full series based on the premise and in 2008, “Supersizers Go…” premiered to critical praise.

While I agree that the show is television at its best, blending history, gastronomy and comedy in brilliant and hilarious ways, there are also plenty of moments, like the snark about Edwards Fletcherism, that drew my attention in particular. So, today I would like to go through all six episodes of “Supersizers Go…” to share what I’ve learned, and cringed at, from the show.

All of the episodes are currently available on YouTube, but I recommend watching them quickly before some dickweed decides to report them.

Supersizers Go Wartime (1940-1945)

During World War II, Britain rationed food to conserve commodities for the war effort. But unlike World War I, when rations were strategically, rather than nutritionally, planned, the WWII rations were intended to benefit the home front as well as the battle front, according to the physician Giles consults at the beginning:

This wartime diet that you’re about to do was scientifically devised to put people into a state of health, in fact put the entire population in a state of health… Psychologically, you may actually experience a feeling that this is rubbish grey food simply because it’s not as exciting, as fun. It’s a greyish diet.

I love how the doctor explains what Giles and Sue should expect because it implies that the view that “rubbish grey food” is not exciting or fun is a psychological problem, rather than the fact that “rubbish grey food” is just not exciting or fun.

This, in a nutshell, is how the medical establishment views caloric restriction for fatties: just because food is grey and bland doesn’t mean it’s not exciting or fun! And, indeed, the food Giles and Sue consume throughout the week are meager, barely-seasoned meals.

Of course, Giles the Glutton puts the diet into perspective:

It will be a high price to pay for a little extra fitness.

While meat, milk, butter and eggs may have been scarce, vegetables (root vegetables in particular) were available in unlimited quantities and Brits were encouraged to plant their own “victory” gardens to support the war effort. In the span of a single generation, British society went from the unrestrained excess of the veggie-less Edwardians to a society thrust into a near-vegetarian diet.

The effects were remarkable:

The consumption of sugar and fat having been cut by 50%, rates in heart disease, obesity and diabetes dropped to levels dramatically lower than today.

Many look back on this time as a though those who lived through World War II were more disciplined and restrained than us modern, lazy gluttons. If only we had the character and fortitude of our forbears, we, too, could be thin like them.

Yet this view overlooks one particular problem: the rationing “diet” was not optional. Just as contestants on The Biggest Loser submit their dietary autonomy to “experts” until they lose the weight, the wartime population did not have a choice in their diet.

Although there was one area of wartime Britain unaffected by the rations: restaurants.

As a result, dining out became hugely popular during the war because of the convenience and pleasure of delicious, substantive food. Plus, allowing another person to prepare and clean up after the meal meant husbands and wives could spend more time enjoying each others’ company.

These are some of the same reasons people are eating out today more than ever: due to the two income trap, parents are working harder and longer hours and often just want someone else to take over the duties of cooking and cleaning up after meals. It’s a completely reasonable explanation, and Giles tries to distinguish between the habits of fat modern Brits are compared to the thin wartime Brits:

If they look at us today and how fat we’ve become, this illusion of choice, the crisps and the chocolate, the rubbish we eat all the time. I think we’re probably more miserable, more run down and less healthy than they were.

Even if wartime Brits were less miserable, less run down and more healthy than we are today, it wasn’t their choice. It’s easy to look back and glamorize the wartime rationing as the ideal diet for a nation, but I doubt those who had to make those sacrifices for the full five years, rather than a mere week, would rather choose rations of dietary freedom.

But our society likes to rationalize our current obesity rates as a result of a flawed people who lack the self-discipline to live by the austere menus of wartime rationing. Both Giles and Sue seem to make the incredible claim that our modern culture has less dietary choice than wartime Brits.

Sue says:

I think the modern diet people think is about choice, but actually but it’s about slavery to big brands and junk and rubbish that nutritionally we don’t need and we don’t really want.

These simplistic explanations for why people eat the way they do today completely ignore the reality of contemporary culture, which doesn’t impose limits because of slavery to big brands, but because our society has less time and less money to prepare and cook the kinds of meals available during World War II.

People choose big brands today for the same reasons that restaurants flourished during the War and the wealthy had massive teams of cooks preparing each and every meal: convenience.

It’s a theme we’ll see again and again throughout the series.

You can check out the full menu at JustHungry.com.

Supersizers Go Restoration (1660-1685)

In the 17th century, water was contaminated and milk was unhealthy, so the only beverages available were wine and ale. Of course, it also probably helped to face the food of the day, such as stuffed ox tongue wrapped in a calf’s amniotic sack.

Like the Edwardian period (and pretty much every epoch before the 20th century), the main focus of the meal is meat, meat and more meat. It seems that History has long leaned toward the low-carb Atkins diet, from carp to eel pie to Olio Podrida, a dish served with over 20 kinds of meats all mixed together. Here’s the week’s menu.

While the wealthy gorged on animal flesh, author John Evelyn ushered in the dawn of vegetarianism and reassured the population that vegetables were not only safe to eat, but actually good for you.

Once again, fatness is an issue during the Restoration and Sue tries a “cure for cellulite” from the time, which was advertised as “for big bellied women in need of self-governance.” The cure was a bath of claret wine infused with wormwood (the psychotropic agent in absinthe), mint, chamomile, sage and squinath (a flowery reed).

Supersizers Go Victorian (1837-1901)

We all know the Victorian era as a time of austerity, modesty and deprivation. Of course, with rampant poverty this wasn’t a problem for most of the population, which subsisted on tea and bread.

This was also the era when colonists began sending back sugar from the colonies. During Queen Victoria’s 63-year reign, sugar consumption jumped from 15 to 90 pounds per person per year. And that was back when sugar was expensive and rare. Today, with sugar cheap and plentiful, we’re up to around 156 pounds per year.

The Supersizers blame sugar on Victoria’s toothlessness and the fact that, as Giles says, she was “fat as a house.” This also leads to Giles making the dickish comment that “I don’t want a bloater for a wife, so I sent Sue for a health check.”

For the wealthy, some fruits and vegetables began gracing the meat buffet that was Victorian dining, but meat is still king. In what chef Sophie Grigson describes as a “plain family dinner menu,” Giles and Sue are served a whole boiled calf’s head with brains on the side. You can read the whole menu here.

Meanwhile, the poor (aka, the rest of England) had to subsist on the meager rations. As charity became fashionable for the wealthy, Sue heads to a soup kitchen where she recreates a Victorian menu for feeding 20 poor people with a single bowl of soup. The recipe called for one ounce of lard dripping added to two gallons of water, a quarter of pound of leg of beef without bone, turnip peelings, leaks and flour.

Once again, forced caloric restriction kept the poor thin and access to savory and delicious foods may have contributed to Victoria’s obesity, but the deciding factor is not so much moral character as accessibility.

In this episode, the odd thing is that with access to this diet, Sue consumes 20,000 calories over the course of a week, doubling her typical intake. Using the Calories In/Calories Out Rule of 3,500 calories in a pound, we would expect her to gain approximately three pounds (assuming no difference in physical activity). Instead, she gained seven pounds.

Throughout the series, the diets will periodically defy this prediction, most noticeably in the second season episode of The French Revolution, an absurdly decadent period during which both Giles and Sue both lose weight.

Supersizers Go Seventies (1970-1979)

Considering the fact that the 70s is when the Fat Panic began, it’s interesting to see what people were eating back then. But this episode also contains some information that I have been attempting to wrap my brains around since hearing it. The 70s ushered in the modern convenience food era, with the most popular foods relying on recently developed techniques for freezing and preserving foods. Meat was still king with red meat consumption double what it is today.

But here’s the enigma: according to Dr. Anton Immanual, Consultant Gastroenterologist at University College Hospital, people in the 70s took in 750 more calories per day. Later in the show, Giles claims that they also expended 800 more calories per day through exercise. This, he says, explains why even though people in the 70s ate more food, they remained thin.

But it doesn’t add up at all.

Calories In/Calories Out, right?

So, let’s say for argument’s sake that the average diet today is 2,000 calories. That would mean that the average 70s diet was 2,750 calories, but after exercise, that would leave a daily caloric intake of 1,950 calories. So with a 50 calorie daily increase (18,000 calories per year) that would suggest a gain of 5 pounds per year. So, three decades later, we should have seen an average weight gain of 150 pounds.

Of course, we didn’t start with a 50 calorie daily surplus, so it would be tempered some by the gradual increase. But even a gain of 50 pounds is grossly overstated according to a 2003 article in Harvard’s Journal of Economic Perspectives (PDF):

In the early 1960s, the average American adult male weighed 168 pounds. Today, he weighs nearly 180 pounds. Over the same time period, the average female adult weight rose from 143 pounds to over 155 pounds

This same report found that between 1978 and 1996, men consumed 268 more calories per day and women consumed 143 more calories. Even with these caloric surpluses, the author’s admit the estimates don’t add up, as men would consume an average of 100,000 more calories per year and 50,000 for women. This would suggest an average annual weight gain of 29 pounds for men and 14.5 for women. And that’s just one year, not the 40-odd years of their assessment.

Once again, simplistic assessments of caloric balance do not explain contemporary obesity rates at all.

Oh yeah, and you can read the menu here.

Supersizers Go Elizabethan (1558-1603)

As with the other eras, the Shakespearean diet boasts a meat-heavy diet (menu here), best exemplified by hodge podge, a pie of many meats like the Olio Podrida. But their diet also upends much of our assumptions about historical diets.

For instance, you can’t throw a stone without hitting a proponent of the “white bread makes us fat“) argument, such as Walter Willett and David Katz. Yet in Elizabethans ate between two and five pounds of Manchet bread per day. Today, Britons eat approximately 1.5 pounds per week. And Manchet bread is white bread because, as one historian in this episode put it, “The whiter the roll, the more expensive the loaf.”

So, we begin with the doctor examining both Giles and Sue. He comments on the fact that Sue’s BMI is 20, on the low side of “normal,” while Giles is barely in the overweight category. To this, Giles says, “So basically Miss Teetotaller, vegetarian goody-two-shoes is going to live forever.” All this based on BMI.

And yet after a week on meat, meat, meat, meat and Manchet bread, both Sue (9 pounds) and Giles (7 pounds) lost weight and lowered his cholesterol. The reason, the doctor explains, is that meat is an appetite suppressant. Yet the two ate a combined 40,000 calories in one week.

Even with the contradictory evidence, Giles still comes to this baffling conclusion: “And that’s why in these times people didn’t live very long.”

Supersizers Go Regency (1811-1820)

The Regency era and the days of Jane Austen have to be the most appetizing meals covered by this series, as evidenced by the menu.

But once again we are introduced to this menu through the weight of the Prince Regent, George IV, who weighed 280 pounds and suffered from gout. On the other end of the spectrum, we have Lord Byron, who was notorious not only for his outrageous lifestyle, but his bulimia and manorexia as well.

But what defines this era’s diet most, in my opinion, was the Enclosure Act, which stripped the rights of commoners to use common land for cultivation, as well as made the hunting of wild game illegal. Wealthy land-owners were allowed to shoot poachers on site, leading to a drastic change in the diets of the poor.

Meanwhile, the wealthy subsisted on approximately 5,000 calories per day and the disease of kings, gout, became common place. In fact, Giles himself repeatedly tests high for uric acid, the primary risk factor for gout.

Which brings me to an interesting observation on this show. Here is Giles taking off his shirt:

It is only because Giles appears thin that he is able to start in a series that features some of the most decadent, indulgent, and unhealthy foods known to man, and define himself as an “unashamed glutton” without the concern trolls descending like locusts to tell us what a horrible, horrible show this is.

Yet we can see in the exams that the physicians put him through that his metabolic indicators aren’t the best. He’s a thin guy who indulges in hedonistic pleasures, but because his body does not reflect that gluttony, he can revel in that excess without consequence (though he claims to work out, but as any fitness buff will tell you, you can’t counteract “bad” food with “good” exercise).

But at the same time, Giles, who admits that his normal diet isn’t far from the French Revolution diet in terms of quantity, spends much of the series pointing out the weights of the aristocrats and royalty who were able to live on these diets because they had the access and means to do so.

What I find most interesting in this series, though, is how it peels back the layers of complexity in our “choice” of diet. Throughout history, the wealthy have been able to indulge in delicious foods that they didn’t have to cook, and it has never, ever been an issue in society. Those foods may have still contributed to obesity, but the fact that having access to those foods meant you ate them was a no-brainer.

Now, today, when we’ve developed a food system that makes it possible for even the poor to have access to delicious foods they don’t have to cook, we declare war on those whose bodies appear to reflect that diet.

It’s just like when Jillian Michaels says it’s okay to give your kids ice cream, as long as it’s the expensive organic coconut kind. The problem isn’t that people have historically enjoyed to eat food that is supposedly unhealthy for you, it’s that when you let the poor do it, they all get fat and gross.

And so, being able to control the diets of the poor has become more about forcing the kind of restrictions that were once the natural effect of class, or rations. It’s not that society isn’t okay with people enjoying decadent meals, it’s that society hates the idea of the poor taking pleasure in what was once strictly the province of the wealthy.

And by poor, that’s anyone who isn’t a millionaire at least. If your income isn’t in the 7-figure per year range, forget about being able to eat those yummy foods and be/stay fat without being reviled.

Anyone who has to worry about how the bills will be paid if they lose their job, or anyone who doesn’t have a small fortune in savings to fall back on can forget about having any privilege relating to food and being fat. Of course, all bets are off if you’re in the public eye - as in being an actor/actress or a politician. Then it’s open season on you, your weight, what you eat, and whether you exercise or not (and how much you exercise).

It’s almost like a jealousy thing. People are jealous that they don’t get to be the King with all the good food and the servants, so they insult his weight. Well, given the opportunity, I’m certain they would take advantage too. And if you saw some of the privileges they got as kings, you’d be jealous too.

Peace,

Shannon

as a fellow fan of the show you will be glad to know they show then often on the cooking channel.

Awesome. I don’t have cable, but I’m glad they’re out there.

Peace,

Shannon

“Of course, it also probably helped to face the food of the day, such as stuffed ox tongue wrapped in a calf’s amniotic sack.”

I quit, ick.

Yeah, that’s the one that stood out for me too (the sack looks like a giant, snotty spiderweb), but it is by no means the grossest thing they ate. I’m pretty sensitive to gross food (I hated Fear Factor), but you just have to watch it anyway. It really is a brilliant show.

Peace,

Shannon

I love this show. It’s hilarious and educational, if you can close your ears to the occasional ‘hur hur fatties’ moment.

Just for the record, one month of each year I do a purely forties diet and lifestyle for fundraising purposes - rationing and all. For the first week I always go slightly nuts: I suspect it’s the lack of my usual processed foods such as soy milk, that contain sugar and preservatives. Then my body settles down into the routine of increased exercise, hugely vegie-based diet, boring meals and having to set my blinking hair every week.

At the end of the month? Yes I generally feel pretty good and no I don’t tend to lose much, if any weight. I know it’s only a month, and a sample size of one person isn’t any kind of evidence, but I do think it’s interesting how many people seem to think there were no fat people back then (look again, folks) and that everybody was super-healthy.

I do think my body really enjoys that diet, but it’s very difficult in terms of time spent in shopping, cooking (and balancing ration-books), and given a choice of living now and living then, I choose now every time. In a world without antibiotics, but with V2s flying around, fat arms would be the very, very least of my troubles.

Len,

I’m curious, what are you raising money for with your 40s diet? That sounds really interesting. You should let us know when you’re doing it again, as I’m sure some people here would donate to your cause.

Also, do you ever have your bloodwork done before and after? That would be an interesting comparison as well. I’m sure that if we were forced to live the 40s diet (as people in the 40s were) there would be an improvement in health (even without weight loss), but whoever enforced the nationwide diet would likely have a rioting horde on their hands.

Peace,

Shannon

Fascinating post about a fascinating program which I haven’t managed to catch nearly enough episodes of. Same sort of misgivings about the fat-related comments, though.

On WWII, I recall someone pointing out that while the population was supposedly ‘healthier’ back then, the average British woman went up one or two dress sizes. (Which must have been awkward, given that clothing was also rationed.) I used to have a copy of We’ll Eat Again, a book of rationing recipes compiled by Marguerite Patton, a Ministry of Food advisor and cook at the time - even she said in the intro that in hindsight, she didn’t realize just how tired all those ladies were at having to concoct yet another cabbage-based meal. There was also the issue that given the traditional emphasis on the working man and/or the growing children needing more food, some women would go without their own ration of, usually, meat or cheese so the rest of the family had enough - there was one Government ad in the book aimed at convincing people that ‘She (a tiny little woman) needs as much protein as he (a huge muscular builder) does!‘ Another ad actually did urge people not to over-indulge and get fat because ‘A large untidy corporation/Is far from helpful to the nation.’ So much for there being no fat people back then!

As for ‘choice’, I’m recalling back when we had that other show, 1940s House - they had a typical 1930s pre-war shop and got the family used to buying goods there, then they brought in rationing and showed them exactly how much less stuff they had access to - I seem to recall the woman of the house actually bursting into tears at that point. It’s probably no coincidence, either, that kids who grew up in the War, with not much in the way of sweets or sugar, tended to have a thing about those foods in later life - I’ve known a fair number of people of that generation who had a very sweet tooth. Really, there’s a lot of mythology about how well us Brits coped with rationing, when I think by the time it ended (well after the War did) everyone was heartily fed up with it. Nanny-state politicians who want to control what people eat might take that in mind.

Oh crap! I can’t believe I left that out. It was in my notes and everything. At the end of the Wartime episode, Sue says that British women went up a dress size, which is yet another contradiction for all those who say a rationed diet would lead to weight loss. In what was essentially a nationwide social experiment, the women gained weight (most likely muscle, though). Putting people on a forced (mostly) vegetarian diet won’t necessarily make them smaller or slimmer. But I’ll bet they were healthy as oxen!

I think if our nation had to introduce rationing for some reason, I’d be weeping too. And I definitely think you’re right about those who lived through that time of deprivation went on to compensate after the rations were lifted. It’s just human nature. It happened here with the Great Depression too. When a population is temporarily denied the freedom of choice, when that freedom is restored they will have a newfound appreciation for that choice, and take advantage.

And I definitely think you’re right about those who lived through that time of deprivation went on to compensate after the rations were lifted. It’s just human nature. It happened here with the Great Depression too. When a population is temporarily denied the freedom of choice, when that freedom is restored they will have a newfound appreciation for that choice, and take advantage.

Speaking of Nanny-state politicians, have you seen this: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-17705228

Although the Guardian article on the subject suggests they’re going after the food industry which, in a way, I don’t have a problem with. Limits on food advertising? Meh. Doesn’t really affect my freedom, so I’m mostly okay with it. It’s when they start making weight loss a national priority and talking fat taxes (as they do in this article) that I start to get pissed.

Peace,

Shannon

The last time I checked, potatoes are a vegetable & a very nutritious one. I always wonder why so many people give potatoes short shrift when discussing vegetables. The potato provides more nutrients than perhaps any other one vegetable, which is why Ireland did so poorly during the potato famine. Other vegetables are fine, but I hate to see so many people treat potatoes as if they have no value or are almost some kind of junk food. Potatoes provide fiber, protein, a large amount of potassium, as much vitamin C as an orange, some B-vitamins & other trace vitamins; it is indeed possible, so I have read, to be adequately nourished on potatoes & milk, supplemented with a little beef or oatmeal.

Interesting program & indeed they get away with it because they are thin. Fat people on average eat no more or differently than thin people, but we cannot get away with appearing to enjoy our food ‘too much’ or playfully calling ourselves ‘gluttons’. Others will do more than enough of that.

I had to look up potato nutrition because I do, indeed, think of potatoes as a sort of non-food, and I think it’s all the propaganda about how potatoes (largely in the form of french fries) are responsible for obesity. I’ve always just thought of potatoes as strictly a starch, and didn’t think there was anything substantial to them at all. I’m having trouble confirming the amount of Vitamin C as comparable to an orange (the Mayo Clinic says an orange has the recommended daily value of vitamin C (60 mg), but a potato only has 20 mg of vitamin C). Of course, that’s with the skin on too. I would be curious to learn more about the nutritional composition of potatoes. I bet there’s a book on the subject out there somewhere. Hmmmm… off to search.

Peace,

Shannon

And Queen Victoria, btw, was nearly 82 when she died, which was a very good lifespan back then & a pretty decent one now.

That’s awesome. The average lifespan for a female in 1900 was 48. Suck it, haters!

Peace,

Shannon